By Hiran de Silva

This article is inspired by a post from Mike Thomas on LinkedIn.

We are in danger of falling into a lazy trap: projecting today’s technological worldview back into the 1980s as if the people of the time were just “waiting around” for the future we now take for granted.

A recent example of this comes from Mike Thomas, who quipped that “Windows users had to wait two more years for Excel.” Really? Let’s pick that apart.

The Myth of the “Windows Users” in 1985

There were no Windows users in 1985. Windows did not exist as a mainstream platform. It wasn’t something people were sitting at, twiddling their thumbs, desperate for Excel to arrive. The PC landscape was almost entirely DOS, and in the business world, the spreadsheet of choice was Lotus 1-2-3.

The Macintosh? Yes, it had its fans, but its workplace penetration was practically zero. And here’s where present-day hindsight distorts things. When we say “Mac” today, people picture a sleek iMac or MacBook. But the first Macintosh was nothing of the sort.

The Reality of the Early Macintosh

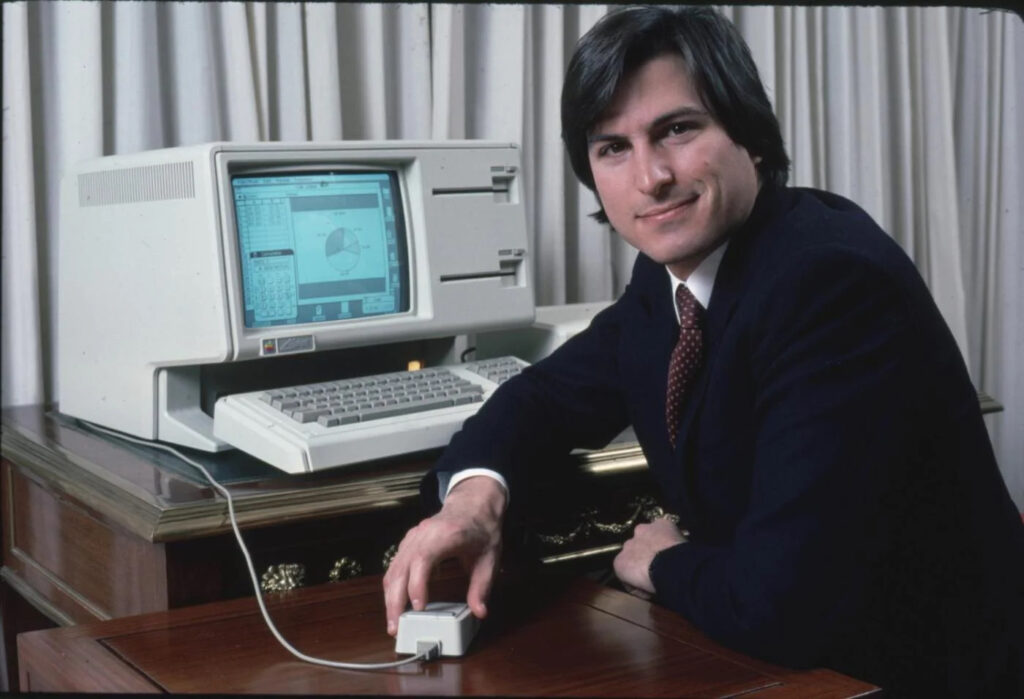

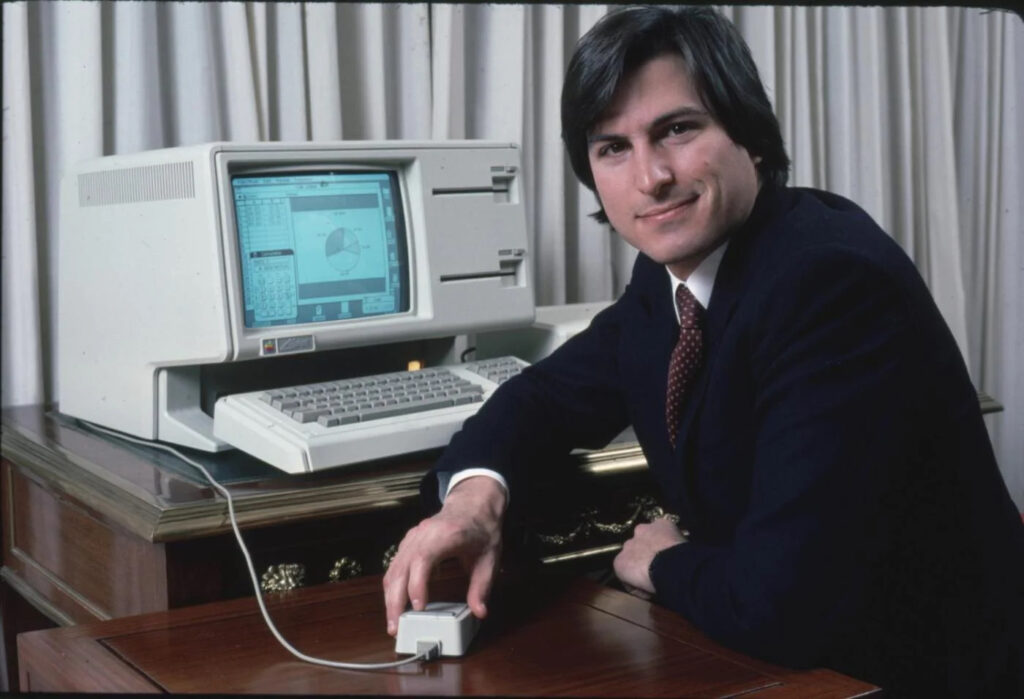

Apple’s GUI journey began with the Lisa, a massive, expensive beast that never gained traction. Steve Jobs then went to the other extreme: a tiny, compact footprint that could sit on a crowded desk. Admirable idea in theory, but disastrous in practice.

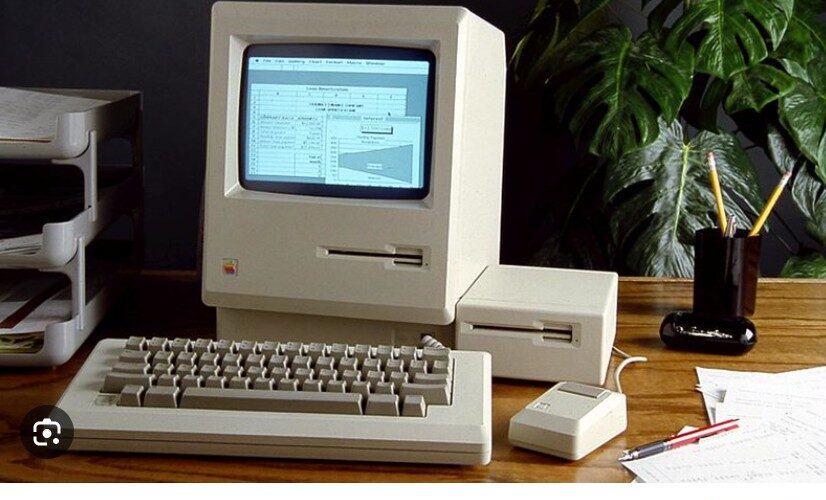

The result was that 9-inch monochrome “doorstop” Macintosh. Small, cramped, and utterly unsuited to spreadsheet work. Imagine trying to scroll through wide financial models on a tiny, black-and-white square screen. It wasn’t viable.

I remember Apple’s own promotion in June 1985—take one home for the weekend. I did. I ran Microsoft Multiplan on it (the spreadsheet that actually ran on Macs at the time). It was a novelty. But I was already using Multiplan on a proper DOS PC at work, and the difference was night and day. The Mac was fun to play with, but nobody serious about spreadsheets or business processes was using it.

So yes, Excel technically “launched” on the Macintosh in 1985. But to say that mattered in the business world is rewriting history. It didn’t.

The Real Market Context

In 1985, the battlefield looked like this:

- Lotus 1-2-3 ruled the spreadsheet market on DOS.

- WordPerfect was king for word processing.

- DOS ruled the desktop, with its green text on black screens.

- GUI-based machines—Atari, Amiga, Macintosh—were niche, enthusiast toys, not enterprise tools.

The idea that DOS office workers were gazing over at Mac owners thinking, “Can’t wait until Excel arrives for Windows” is absurd. Many weren’t even convinced Windows would survive at all—Apple was suing Microsoft over “copying the GUI,” and most of the business world was quite content in the green-on-black universe of DOS.

When Excel Really Arrived

Excel’s true arrival wasn’t in 1985, and it certainly wasn’t with the Mac release. It came in 1989, with the rise of Windows 3.0 and cheap VGA colour displays (a dazzling 16 colours at the time).

Now Excel had an environment where it could shine—pull-down menus, mouse support, colour charts. Compared to Lotus on DOS, it was a revelation. Still, output meant dot-matrix printers churning out 80- or 132-column grids. WYSIWYG was more promise than reality.

Why Excel Beat Lotus

Excel didn’t win because Windows users “waited two years.” It won because Windows displaced DOS, and Lotus failed to adapt. By the time Lotus finally released a credible Windows version in the early 1990s, the market had already moved. Microsoft bundled, integrated, iterated, and Lotus was eventually swallowed by IBM—discontinued in 2013.

The Lesson

History isn’t a cartoon where today’s winners were always destined to win. To claim otherwise is to flatten the genuine uncertainty and messiness of technological progress. In 1985, no one thought of Excel as inevitable. Most hadn’t even heard of it.

Excel’s dominance wasn’t about users “waiting patiently.” It was about timing, environment, and seizing the moment when the platform shifted.

And finally …

Nobody knew anything called WW1 until WWII arrived. It was called The Great War. Nobody knew Excel until it was released for Windows. Effectively, it did not exist in the business world.

Rewriting Excel History from Today’s Perspective

Alternative article. Extended.

We are in danger of falling into a lazy trap: projecting today’s technological worldview back into the 1980s as if the people of the time were just “waiting around” for the future we now take for granted.

A recent example of this comes from Mike Thomas, who quipped that “Windows users had to wait two more years for Excel.” Really? Let’s pick that apart.

The Myth of the “Windows Users” in 1985

There were no Windows users in 1985. Windows did not exist as a mainstream platform. It wasn’t something people were sitting at, twiddling their thumbs, desperate for Excel to arrive. The PC landscape was almost entirely DOS, and in the business world, the spreadsheet of choice was Lotus 1-2-3.

The Macintosh? Yes, it had its fans, but its workplace penetration was practically zero. And here’s where present-day hindsight distorts things. When we say “Mac” today, people picture a sleek iMac or MacBook. But the first Macintosh was nothing of the sort.

The Reality of the Early Macintosh

Apple’s GUI journey began with the Lisa, a massive, expensive beast that never gained traction. Steve Jobs then went to the other extreme: a tiny, compact footprint that could sit on a crowded desk. Admirable idea in theory, but disastrous in practice.

The result was that 9-inch monochrome “doorstop” Macintosh. Small, cramped, and utterly unsuited to spreadsheet work. Imagine trying to scroll through wide financial models on a tiny, black-and-white square screen. It wasn’t viable.

I remember Apple’s own promotion in June 1985—take one home for the weekend. I did. I ran Microsoft Multiplan on it (the spreadsheet that actually ran on Macs at the time). It was a novelty. But I was already using Multiplan on a proper DOS PC at work, and the difference was night and day. The Mac was fun to play with, but nobody serious about spreadsheets or business processes was using it.

So yes, Excel technically “launched” on the Macintosh in 1985. But to say that mattered in the business world is rewriting history. It didn’t.

The Real Market Context

In 1985, the battlefield looked like this:

- Lotus 1-2-3 ruled the spreadsheet market on DOS.

- WordPerfect was king for word processing.

- DOS ruled the desktop, with its green text on black screens.

- GUI-based machines—Atari, Amiga, Macintosh—were niche, enthusiast toys, not enterprise tools.

The idea that DOS office workers were gazing over at Mac owners thinking, “Can’t wait until Excel arrives for Windows” is absurd. Many weren’t even convinced Windows would survive at all—Apple was suing Microsoft over “copying the GUI,” and most of the business world was quite content in the green-on-black universe of DOS.

When Excel Really Arrived

Excel’s true arrival wasn’t in 1985, and it certainly wasn’t with the Mac release. It came in 1989, with the rise of Windows 3.0 and cheap VGA colour displays (a dazzling 16 colours at the time).

Now Excel had an environment where it could shine—pull-down menus, mouse support, colour charts. Compared to Lotus on DOS, it was a revelation. Still, output meant dot-matrix printers churning out 80- or 132-column grids. WYSIWYG was more promise than reality.

Why Excel Beat Lotus

Excel didn’t win because Windows users “waited two years.” It won because Windows displaced DOS, and Lotus failed to adapt. By the time Lotus finally released a credible Windows version in the early 1990s, the market had already moved. Microsoft bundled, integrated, iterated, and Lotus was eventually swallowed by IBM—discontinued in 2013.

The Lesson

History isn’t a cartoon where today’s winners were always destined to win. To claim otherwise is to flatten the genuine uncertainty and messiness of technological progress. In 1985, no one thought of Excel as inevitable. Most hadn’t even heard of it.

Excel’s dominance wasn’t about users “waiting patiently.” It was about timing, environment, and seizing the moment when the platform shifted.

Add comment