Why the Excel Replacement Industry Is Fighting the Wrong Battle

By Hiran de Silva

Triple Your Pay With Excel

For clarity, let me begin with an important distinction.

This article is not a criticism of Excel users.

It is not a criticism of the Excel community.

Nor is it a criticism of the many educators who teach Excel skills online.

In fact, the Excel replacement industry begins with an observation that is entirely correct.

Most spreadsheets used in business today behave like documents.

A person sits at a computer.

Data is imported into a workbook.

Analysis is performed locally.

The workbook is then emailed, shared, or passed on to someone else.

That description is accurate.

But what happens next is where the problem begins.

The industry takes a true observation… and draws a false conclusion.

The Observation They Exploit

If you diagram how spreadsheets are commonly used, you see a familiar pattern.

All arrows point inward toward a single workbook.

Data is gathered.

Processing happens inside the file.

Outputs are created.

The file is sent onward.

The spreadsheet behaves like a digital document — a modern equivalent of paper moving between departments.

The Excel replacement industry points to this reality and declares:

- Spreadsheets are fragile

- Spreadsheets do not scale

- Spreadsheets cannot support enterprise collaboration

- Excel belongs to a bygone technological era

This narrative is widely repeated.

It is also historically wrong.

To understand why, we need to revisit how business computing actually evolved.

Computing Before the 1990s

In the 1980s, desktop computers were called microcomputers.

They operated under systems such as CP/M and DOS.

These machines had a critical limitation:

Only one application could run at a time.

Every software package had to contain everything it needed within itself:

- the screen layout

- the business logic

- the user interface

- and the database storing the data

Accounting systems contained their own data.

Payroll systems contained their own data.

Stock systems contained their own data.

If one department needed information from another, collaboration meant physically moving information:

- printing reports

- copying floppy disks

- manually re-entering data

Sending physical media was collaboration.

This architecture was not poor design.

It was technological necessity.

The hardware demanded it.

The Revolution That Changed Everything

Around 1990, two developments transformed computing forever:

Windows and networking.

Computers could suddenly run multiple applications simultaneously.

That change created an obvious question:

Why keep data trapped inside individual applications?

Why not centralise it?

Instead of many isolated databases, businesses began storing data in one central location.

Applications became clients.

The central database became the server.

Thus, client-server architecture was born.

This shift powered the rise of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems and dramatically increased global productivity.

It was one of the most important technological transitions in modern business history.

The Part Most Narratives Leave Out

Here is the crucial fact rarely acknowledged in discussions about Excel.

Microsoft Office was built during — and for — this client-server era.

Excel, Word, Access, and PowerPoint were not designed as isolated tools.

They included built-in connectivity specifically intended to interact with centralised data systems.

Technologies such as:

- ODBC

- ADO (ActiveX Data Objects)

- database drivers integrated into Windows

have enabled Office applications to connect directly to databases for more than thirty years.

Excel did not miss the enterprise revolution.

Excel participated in it.

Quietly.

Continuously.

And largely unnoticed.

What Excel Can Actually Do

Modern Excel is fully capable of operating as a client in a client-server architecture.

An Excel workbook today can:

- connect to cloud databases

- query live enterprise data

- update shared records

- participate in automated workflows

- support large-scale collaboration through centralised data

In architectural terms, Excel behaves no differently from:

- a web application

- a mobile app

- or enterprise planning software

Because architecture is not defined by the application interface.

Architecture is defined by where the data resides.

Separate the data from the workbook, and Excel becomes part of an enterprise system.

The False Comparison Behind “Excel Hell”

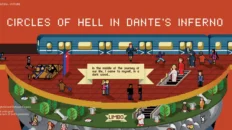

This brings us to the famous narrative often promoted by vendors and analysts — the idea of the “Nine Circles of Excel Hell.”

The argument typically compares modern cloud platforms with spreadsheets exchanged by email.

But this comparison contains a fundamental flaw.

It compares today’s enterprise applications with spreadsheet practices shaped by 1980s technological constraints.

It assumes Excel itself is limited to those historical practices.

That is equivalent to comparing a modern car with a horse-drawn carriage and concluding that automobiles cannot evolve.

The reality is simpler.

Excel is not stuck in the 1980s.

Certain usage habits are.

The Thanksgiving Turkey Problem

There is a well-known story about a family Thanksgiving tradition.

Each year, the turkey is cut in half before being placed in the oven.

Generation after generation follows the ritual faithfully.

Until one day, a grandmother explains the origin.

The original oven was too small.

The turkey was cut simply so it would fit.

The modern oven is large enough for the whole bird.

But the habit remained long after the constraint disappeared.

Many organisations still use spreadsheets as documents for the same reason.

Not because Excel requires it.

But because history once did.

The Miracle of Excel

Here is the paradox few people discuss openly.

A ubiquitous tool costing roughly £12 per month — Microsoft 365 — already contains the capability to implement enterprise-grade client-server systems.

Yet an industry worth tens of billions of dollars has grown around replacing spreadsheets on the assumption that Excel cannot do this.

My work, demonstrations, and case studies aim to show something simple:

When Excel is used within modern architecture — separating data from interface — it can deliver collaboration, scalability, and connected business processes at extraordinary efficiency.

This is what I call the Miracle of Excel.

Not magic.

Not hype.

Just architecture.

The Real Question

The debate should never have been:

Is Excel broken?

The real question is:

Why is Excel still being judged as if it were 1985?

Excel is not limited by history.

Only the narrative about Excel is.

And once you understand that distinction, an entirely different future for Excel — and for the people who master it — becomes visible.

Hiran de Silva

Founder, Triple Your Pay With Excel

Advocate for Enterprise-Grade Spreadsheet Architecture

Add comment