By Hiran de Silva

In the early days of computing—specifically during the 1980s—there was a technical limitation that shaped a generation of spreadsheet users in a rather unfortunate way.

On DOS-based systems, you could only run one application at a time. That meant if you had your spreadsheet open and you wanted to look up something in your database, you had to close the spreadsheet first. This single-threaded environment encouraged a strange but understandable workaround: people started using their spreadsheet application to mimic the behaviour of a database.

In fact, that workaround became so common that software began to be sold with this pseudo-flexibility in mind. Lotus 1-2-3 is a perfect example. The “1-2-3” in its name wasn’t just branding—it denoted:

- Spreadsheet

- Database

- Graphics

It was marketed as an integrated solution, even though by today’s standards it was anything but. This is the context into which Microsoft Excel was born—and what it had to compete with.

The Irony of the Macintosh

Even more ironically, much of this “integration” was being championed on machines like the early Macintosh, which shipped with a 9-inch monochrome screen. Imagine trying to analyse data, manipulate tables, and build charts all within a single application window that small.

Yet some businesses adopted the Macintosh not for its software capabilities, but for a rather surprising reason: it freed up desk space. With its compact footprint, it left more physical room for piles of paper—an advantage in the paper-dominant offices of the 1980s.

And so we entered the 1990s with a generation of users who had learned to use spreadsheets to do the job of databases—not because it was the right tool for the job, but because they had no other choice.

But Then Something Changed

Around the mid-1990s, that constraint quietly disappeared.

Windows had become dominant, multitasking was the norm, and Excel—now matured—gained the ability to connect directly to proper databases. With technologies like ODBC, DAO, ADO, and the ubiquitous Microsoft Access, Excel could now synergistically link to and retrieve data from external relational databases.

No longer did we need to copy data into the spreadsheet.

No longer did we need to force Excel to act as a database.

The right tool could now be used for the right job.

But the Shovel Remained

Yet the mindset did not evolve as fast as the technology.

I often use this analogy:

Before motor cars, every horse-drawn carriage carried a shovel to clean up the horsesh*t. But when we invented the car, we didn’t need the shovel anymore. Still, what if people kept carrying the shovel anyway—out of habit?

That’s precisely what’s happened in the spreadsheet world.

People still talk about Excel as if it should be used as a standalone database. They still teach and build solutions where all the data lives inside the spreadsheet, ignoring the powerful client-server architecture that Excel has supported for nearly three decades.

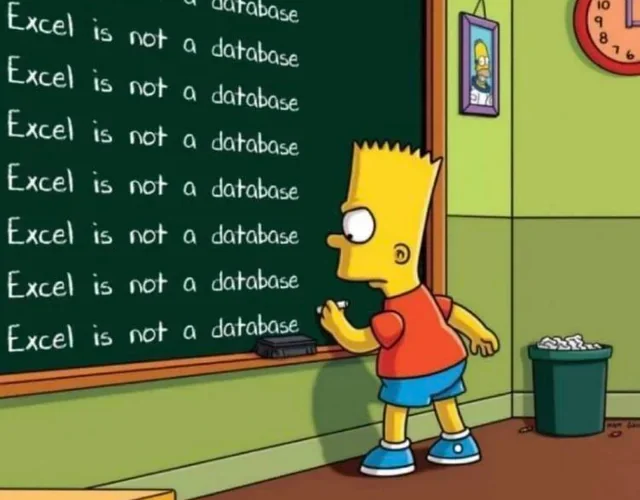

“Excel Is Not a Database” – A Misguided Mantra?

The phrase “Excel is not a database” is now commonly used, but often in an unhelpfully vague or dismissive way. It’s usually said by someone trying to steer users away from poor spreadsheet practices—but rarely followed up with the real solution:

Excel should not be used AS a database. It should be used WITH a database.

This is not just a technical refinement—it’s a game-changing distinction.

- It means Excel can become the perfect front-end for process owners, analysts, and finance teams.

- It means data can be structured, validated, shared, and audited properly in a central relational store (like Access or SQL Server).

- It means users can build scalable, low-maintenance, enterprise-grade solutions without resorting to bloated ERP implementations.

A Call for Contextual Wisdom

So when someone says “Excel is not a database,” let’s not treat it like a meme or slogan on a Simpsons-style blackboard.

Let’s understand the historical context, the technological shift, and the massive opportunity that has opened up since the mid-1990s.

If you’re still building systems where Excel stores all the data, you’re using a shovel in a world of Teslas.

It’s time to retire the shovel.

Add comment